By Dominique Vidalon and Sudip Kar-Gupta

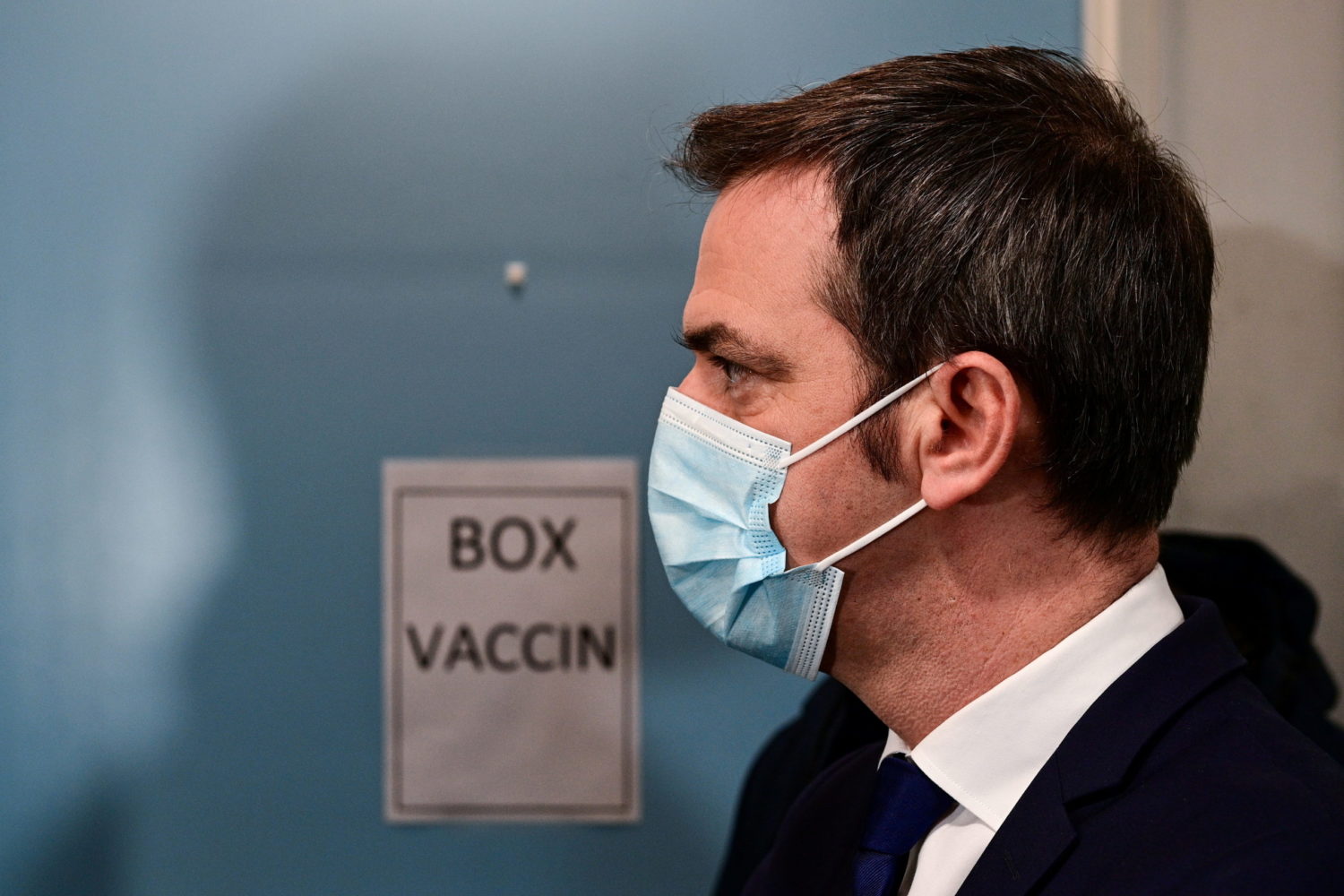

PARIS (Reuters) -France is stepping up its COVID-19 vaccine rollout by widening further its first target group to include more health workers and simplifying a cumbersome process to deliver jabs more quickly, Health Minister Olivier Veran said on Tuesday.

France’s inoculation campaign got off to a slow start, hampered in part by red tape and President Emmanuel Macron’s decision to tread warily in one of the most vaccine-skeptical countries in the world.

But France has fallen behind neighbors such as Britain and Germany, and the president is now demanding the vaccination program be expedited.

Veran told RTL radio that the government was going to “accelerate and simplify our vaccination strategy”.

Some 300 vaccination centers would be operational from next week, the minister said, after initially ruling out such centers.

The original plan had been for the first phase of the vaccine rollout, which began in France on Dec. 27, to focus on nursing home residents and their carers. By the end of the first week, France had delivered just over 500 COVID-19 shots.

Over the weekend, the first hospital staff began receiving the vaccine. The government has now added paramedics and health workers to the first target group.

By the end of January, France will have begun vaccinating people aged 75 and above who are living at home, Veran said.

The head of the union of pharmacies – whose ubiquitous network helps administer millions of flu jabs every year – urged the government to allow it to do the same for COVID-19 shots.

“If we only rely on vaccination centers, we can be sure the level of vaccination by June will be mediocre. That would be a disaster,” Gilles Bonnefond of the USPO pharmacists’ union told, Reuters in an interview. “We can be operational in a week.”

The coronavirus has claimed the lives of 65,415 people in France, the seventh-highest death toll in the world.

France received an initial 500,000 doses of the vaccine developed by Pfizer and Germany’s BioNTech and was due to receive an additional 500,000 per week. It will also get 500,000 doses per month of Moderna’s vaccine once it obtains regulatory approval in Europe and France.

MORE JABS

Rules demanding that only a doctor or a nurse under the direct supervision of a doctor inject the vaccine will be eased. Veran said a doctor would be allowed to supervise multiple nurses at any one time in a vaccination center.

Similarly, rules requiring that any person wanting a COVID-19 vaccine must hold a consultation with a doctor first would also be made simpler.

Veran also said about 10 to 15 cases of the new variant of the coronavirus first seen in Britain had been detected in France. Its rapid spread through southern England compelled British Prime Minister Boris Johnson to announce a third nationwide lockdown on Monday.

France remains under nightly curfew. Restaurants, bars, museums and cinemas are still closed. Veran said he hoped France would be able to open its ski resorts for the February holidays, but that such a move would depend on how active the virus was.

(Reporting by Dominique Vidalon, Sudip Kar-Gupta and Michel Rose; Writing by Richard Lough; Editing by Ed Osmond, Raissa Kasolowsky and Alex Richardson)